You’ve waited long enough! Hopefully you’ve read Part One where I talk about building a receptive table to your teach, as well as Part Two where I talk about introducing the game folks who have committed to playing. Now we get down to actually teaching and playing it!

IV. Teach People How to Play

8) Explain Player Abilities, Resources, and Actions (a.k.a., how they can win)

9) Describe Obstacles and Resistance (a.k.a., how they can lose)

10) Flesh Out the Endgame

11) (Selectively) Talk about Character Powers, Special Cards and Basic Strategies

V. Teaching During the Game

12) Explain Actions As You Play

13) Continue to Learn the Game (and learn how to teach it)

IV. Teach People How to Play

8) Explain Player Abilities, Resources, and Actions (a.k.a., how they can win)

I’ve seen a huge variety of ways that teachers approach explaining the core mechanisms of a game. Some teachers really love going through the entire round of actions, step by step. Others break things apart in ways that make sense to them. I really don’t think there’s a one-size-fits-all approach, so I will change up my teach to suit the game. However, here are some general observations.

Observations for Content:

a) Describe common player abilities, resources, and actions before describing other elements that might influence game play. The player is the active agent, not the game. One of my favorite teaching videos, Through the Ages by Paul Grogan, begins with him talking players through their player mats, then he goes from there. Some game boards are very pretty and have lots of action spaces that make you want to describe them immediately. Other games have a cool gimmick to them which might tempt you into talking about them first, like the interlocking gears in Tzolk’in: The Mayan Calendar. Don’t be seduced! Wait until players have a sense for what they have and what they can do before describing how those other things work.

b) Distill relevant information. Not everything in a rulebook is relevant. All you need to do is give players enough to get going, and the rest will come with time. I have to admit, though, I have a tough time with this one, especially during a first teach. I can’t always tell the difference between relevant information and skippable minutiae. More than anything else I’ve written here, this skill comes from practice and experience. One thing that does help me in this regard, though, is following this next bit of advice…

c) Do NOT introduce exceptions, special/ unique powers, combos, etc., until later. First, a lot of people won’t remember and you might end up having to repeat yourself later. Second, a lot of special powers in games tend to be contained within decks/ stacks/ bags/ etc. that have not been revealed yet. Instead, I try to focus on things players can see and feel in the moment of the teach.

d) Refer back to victory conditions when explaining actions where possible. Many games present a huge amount of options to a gamer right away. Sometimes players can get so wrapped up in their options that they lose sight of scoring and winning. Reiterating the victory condition, though, is like handing a compass to someone lost in the woods. You’re not telling them exactly where to go. But at least they get a general sense of magnetic north, which will give them some clues on where to go and what to do to get there.

Observations for Method:

a) Go slow, be patient, and insure understanding through questioning and repetition. Nothing stalls a game more than questions and confusion from players who don’t understand what they can do in a turn. Try to insure as much understanding as possible before moving on, either by asking questions (“does this make sense?” “everybody got that?”), or by just repeating core points a few times. They may get sick of hearing it, but at least they’ll remember it!

b) “One mic”. Some overenthusiastic gamers might like to chime in to answer questions or “help” you teach something. As a teacher, you want to politely shut that down. Learners learn best when it comes from one source.

c) Only answer clarifying questions. Players love to ask questions, which is fine if answering helps explain some part of the game more clearly. If they ask about anything else, though, then politely offer to answer their question at the end. More often than not, players will hear the answer to their question if they stay quiet and let you do your thing.

d) Be “handsy” with the game. This goes along with everything I’ve said about showing first, then telling. When explaining any action, don’t be afraid to point, lean over the table, flip cards, move meeples, or do whatever else it takes to physically illustrate examples of any game concept you are trying to teach

e) Have fun! This, along with point a, are probably the most important. The best teachers, whether its for board games, high school French, or anything else, give off the vibe that they are having fun and fully invested in people’s learning.

f) Use player aids? Before listening to the Dice Tower podcast about teaching games, I would have recommended using player aids. However, Tom made a point of saying he doesn’t use them during his teach. He finds that players stick their faces in those things instead of listening to him. Fair point! I personally like using them because I find moving through them in an orderly fashion very helpful. Also, I teach so many games that I have a hard time remembering every action in every game. If it’s there on the player aid, though, I don’t have to worry about it.

9) Describe Obstacles and Resistance (a.k.a., how they can lose)

Once players have a grasp of what they can do on a turn, it’s easier for them to understand how the game and/ or other players fight back.

In worker placement games like Lords of Waterdeep or Viticulture, for example, players can put their meeples on any spot, unless someone gets there first with their meeple. In a cooperative game like Flash Point: Fire Rescue, the players have learned how to put out fire, but then they REALLY understand how important it is after they learn about explosions, walls collapsing, etc.

Some games are structured where active opposition occurs before a player’s turn. In Shadows Over Camelot, each player’s turn consists of two things – bad things happening, then good things happening, in that order. For that game, I find it easier to just go with the flow and explain the bad stuff first.

However, SoC is an exception. I normally prefer to start with all the awesome stuff players can do and go from there.

Any bits of advice I gave in section 8 apply here, as well.

10) Flesh Out the Endgame

As a rule, players love good surprises and hate bad surprises. The worst surprise a player can experience in a game is to lose because of some unexplained game element. Therefore, use this time to reinforce what you said about victory, flesh out how losing happens, and explain anything else people need to know about the endgame, such as endgame triggers, special scoring minutiae, tiebreakers, etc.

- Pro-tip: make sure you clearly communicate the exact endgame trigger. If a game ends immediately when someone hits a threshold, or when everyone has the same number of turns, people really want to know that.

For the most part, describing lose conditions is easy because you’ve already explained how to win. Losing, in most cases, is simply the opposite of winning. Lose conditions become a bigger deal when teaching cooperative games. There’s usually LOTS of ways to lose in some of those.

Finally, some games have special “you better do this or else” conditions that you must explain, even though doing them does not lead directly to winning. The biggest culprit I can think of is the “feed your people” requirement in games like Agricola and Stone Age. Good luck telling someone who just had an awesome turn that they now have to give back their gains because their workers are starving.

11) (Selectively) Talk About Character Powers, Special Cards, and Basic Strategies

Why wait all this time to talk about all of the cool powers that people can do in a game? Isn’t half the fun of a game in the special combos and such? Pandemic would be boring without the Medic curing all of those disease cubes at once. The whole draw of a game like Small World is that every race has special powers to which no other races have access.

That is all correct! However, the essence of what makes these powers so special is that they take all of those wonderful rules you shared and break one or more of them in some way. Therefore, you as the teacher need to lay all of that rules foundation in order to players to really understand how to maximize their fun.

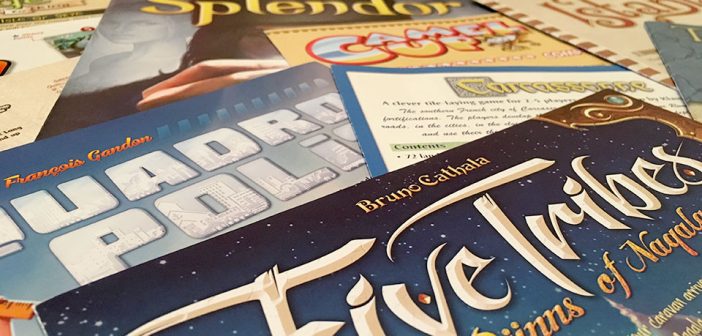

I will definitely describe unique character powers during a teach, since those are generally right in front of the player. However, many games introduce cards and other elements that add further ways to play around with the game system. I am VERY selective with what I show people. I DO NOT show them every card, or even most cards. If you did that for a game like Terraforming Mars with its 250 or so cards in the bast game, you’d be there all day.

Very often, when I set up a game, I cherry pick examples of extra powers that are simple, let you do a cool thing, or are just really powerful cards to look out for. When I set up a King of Tokyo game for a new player, I always put Extra Head in the opening market. It hits all three of these criteria – rolling an extra die every turn is easy to understand, very powerful, and a cool mental image to boot.

Also, I think it’s a good idea to point out any “take that” powers and mechanisms, or other elements designed to screw with people (unless, of course, that’s the whole game). Blood Rage has a lot of cards with cool powers which, for the most part, I leave players to learn about themselves. I do, however, point out some of the Loki cards that allow players to steal those cool powers away from their opponents. That’s a very impactful and, in the right circumstance, frustrating move. People have thanked me for giving them the heads up!

With regard to discussing strategies and combos enabled by these special powers, I try to keep that to a minimum, especially for experienced players. I often find that, at this point in the teach, their mental hamster wheels are already turning and they are ready to go.

However, for some players, their mental hamster is just laying down next to the wheel, dazed, confused, and looking for the next game of Uno. In other words, they are lost and in need of a little bit of guidance. For the sake of someone’s fun, then, I might give them a bit of strategy talk, just to get them going. I might, for example, point out how a card in the market might combo well with their unique player power, or explain how taking a certain resource would benefit them more than taking another.

Again, I will only do this to get people’s minds going. Once a gamer hits that point, though, it’s time to shut up and begin!

V. Teaching During the Game

12) Explain Actions As You Play

If you have a group that just gets it and they don’t need you to talk them through each turn, great! Go with the flow and just have a good time playing.

However, I encounter lots of groups where players still have questions, especially about strategy. Once again, I feel that the best advice is to show first, then tell.

Take the first turn. During that turn and moving forward, do your actions while being very explicit and verbal about why you made those choices. In 7 Wonders, a great first card to take is a resource card because it opens up the ability to build other cards. In Scythe, I will move my pawn to a resource hex, then explain how that move sets me up to build my first mech in x turns. Demonstrate that stuff explicitly during your turn, then talk about it.

Some teachers like to win games that they teach. Personally, I don’t like doing that. Actually, I end up losing regardless because I get so wrapped up in making sure everyone is engaged and having fun. That’s ok, though, because I find that players are generally more likely to have fun and want to play a game again when they are winning, or at least doing well. If the teacher is crushing them, players can become unengaged and disinterested. All of that hard work you did teaching the game gets wasted.

To be clear, I do not advise tanking a game. Rather, I’ll try to explore some kind of suboptimal strategy that I may have been curious about. I love going for wins via technology in Through the Ages, for example. However, if I’m playing against a new player, I might experiment with a military strat. That kind of thing.

Those last two paragraphs come with a giant caveat. This man, designer Eric Lang, would belly laugh my namby-pamby approach. If he teaches you a game, especially one of his own, he will attempt to crush you, break you, and drink your tears. He is a very endearing man, though. I doubt many other game teachers would be able to pull this off.

13) Continue to Learn the Game (and learn how to teach it)

As with most things in life, the more you do a thing, the more you learn about it. As your familiarity with a game grows, you’ll learn about different edge cases and rules wrinkles. I don’t advise working those into your standard teaching spiel, although knowing them will improve your ability to answer people’s questions.

Surely, if the game is any good, you will teach it again to a new group of folks. I try to take note of the kinds of questions people ask during play. If a particular rules question comes up a bunch of times, I will try to incorporate the answer to that question into my spiel the next time I teach it.

Also, I ask for feedback. Did people have fun? Was something unclear? Would they feel comfortable teaching it to others? If they say yes to that last one, then you know you’ve done a good job.

There you go! Years of accumulated wisdom about teaching games. If you missed Part One or Part Two, go ahead and follow those links. I’d love to know how people do it differently, or if they have anything they would add, critique, or change.

I. Personal Prep

1) Learn the Game

II. Draw them in

2) Set up the Board on the Table

3) Give the ‘Elevator Pitch’

4) Finalize the Table: Game Length, Weight, Theme, and Interaction Style

III. Introduce the Game Properly

5) Describe the Theme: “In this game, you are a _____ trying to do ____.”

6) Demonstrate Game Flow: Show First, Then Tell

7) Relate Game Flow to Victory Conditions

IV. Teach People How to Play

8) Explain Player Abilities, Resources, and Actions (a.k.a., how they can win)

9) Describe Obstacles and Resistance (a.k.a., how they can lose)

10) Flesh Out the Endgame

11) (Selectively) Talk about Character Powers, Special Cards and Basic Strategies

V. Teaching During the Game

12) Explain Actions As You Play

13) Continue to Learn the Game (and learn how to teach it)

Show Comments