Scott Pilgrim’s Precious Little Card Game is a thematic deckbuilding card game for 1-4 players, designed by Keith Baker and published by Renegade Game Studios*.

*[I will be working for Renegade Game Studios during PAX Unplugged 2017 and demoing this game. Therefore, in the interest of transparency, I will refrain from giving this game a final score. I hope that my written pros and cons will stand on their own and prove useful to you.]

I’m probably a bit old to go gaga at the prospect of a Scott Pilgrim game. I was born in 1977, so I’m more likely to pop for a Star Wars, Transformers, or He-Man game (He-Man!!!). I was already an old man (according to the high school kids that I taught at the time) when Bryan Lee O’Malley’s graphic novels came out in 2004, and even older when the movie with Michael Serra came out in 2010.

Yet, while I don’t have any kind of primal attachment to the Scott Pilgrim universe, I do enjoy a nice, light, funny theme on a game. And I love quick card games, whether they are competitive or cooperative. As a pleasant surprise, this one offers both modes of play!

With this in mind, I would like to try to answer the following question with this review: do you need to love the IP in order to love Scott Pilgrim’s Precious Little Card Game, or does it do enough to stand on its own and appeal to people who aren’t as attached?

How to play Scott Pilgrim’s Precious Little Card Game (PLCG)

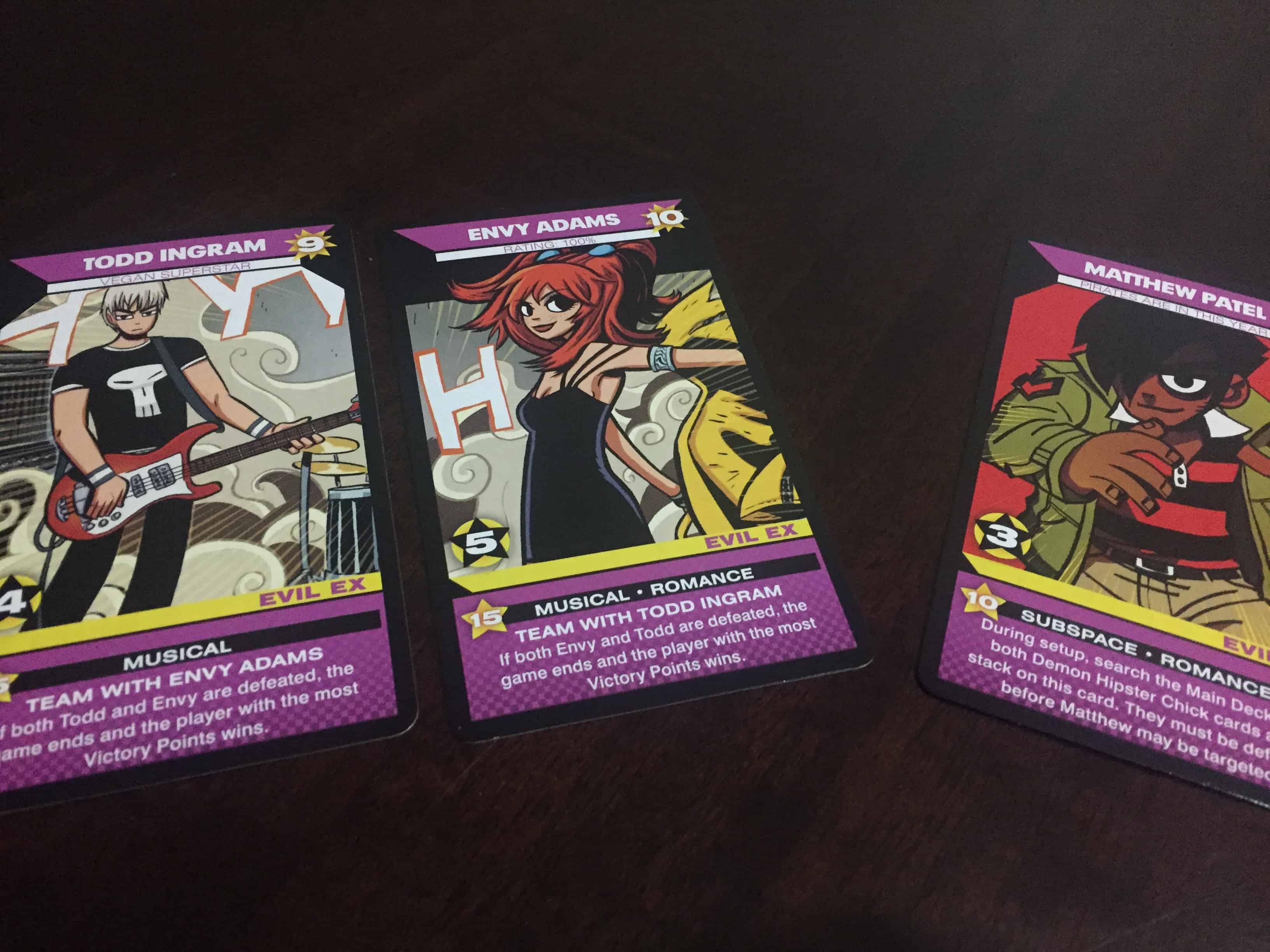

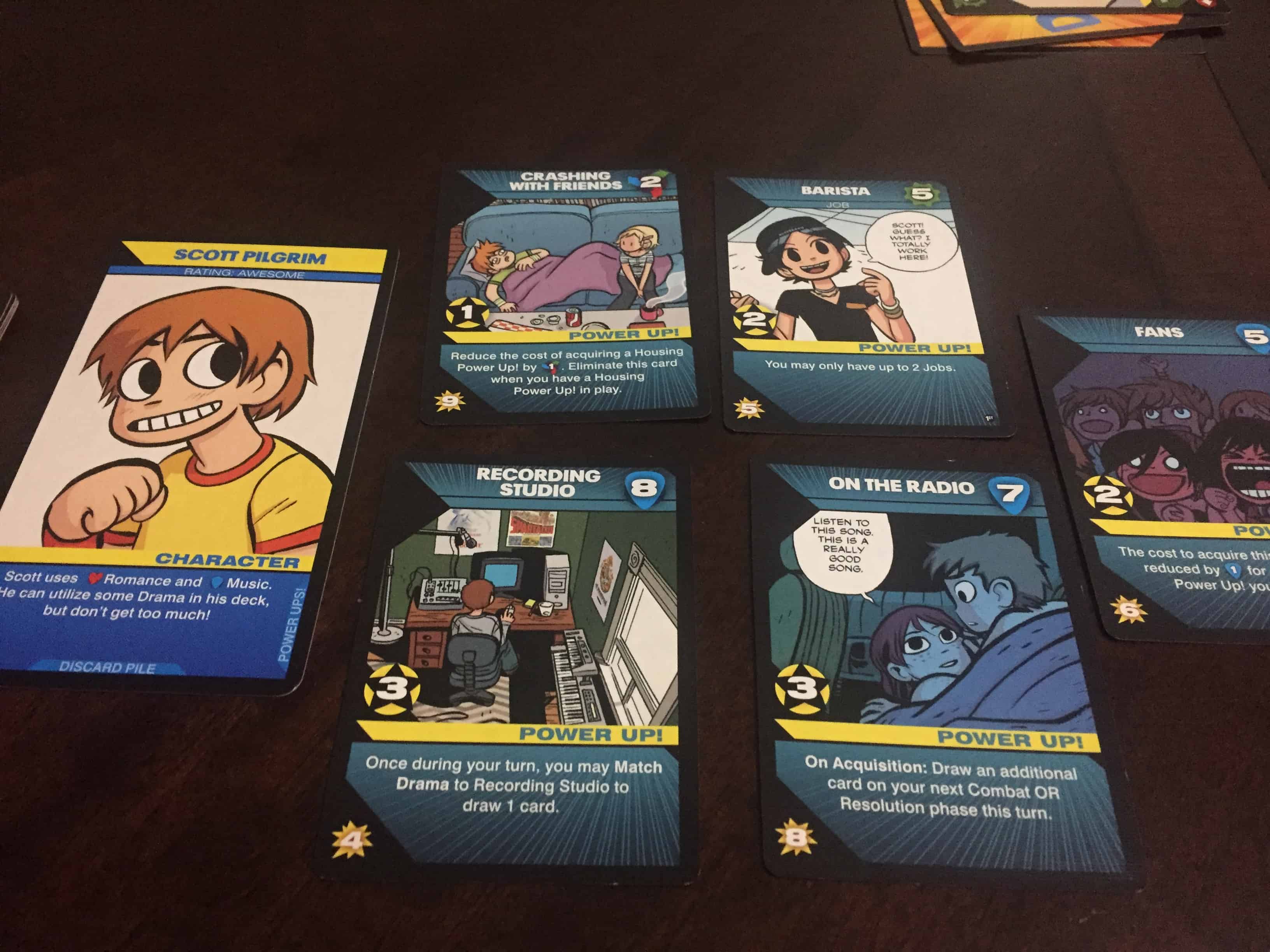

You begin by selecting a hero who, I’m sure, veteran Scott Pilgrim readers/ watchers will recognize – Scott Pilgrim, Stephen Stills, Ramona Flowers, etc. Once you select a hero, you get their oversized character card and, in tried and true deck building fashion, a 10-card starter deck. After that, all players agree upon an “Evil Ex” card which will set the game’s victory point threshold (between 10 and 18 points), as well as some kind of global effect. If you always wanted to stick it to the likes of Envy Adams or the Katayanagi Twins, now you can!

You will notice right away that your starter deck contains double-sided cards, as does the entire 146-card action deck that will make up the market (which this game calls ‘the plotline’). This might seem like a bit of information overload at first, but I don’t think it takes long to get used to it.

The two sides of the cards correspond to the two main phases of the game – acquisition and combat. First, you will go shopping mostly using the green sides of your cards. You can generate and spend three different possible resources (work, romance, and music) to buy better cards from the market. Those new cards will either improve your deck, or will represent friends, jobs, or other fun little story elements that provide static victory points and power-ups.

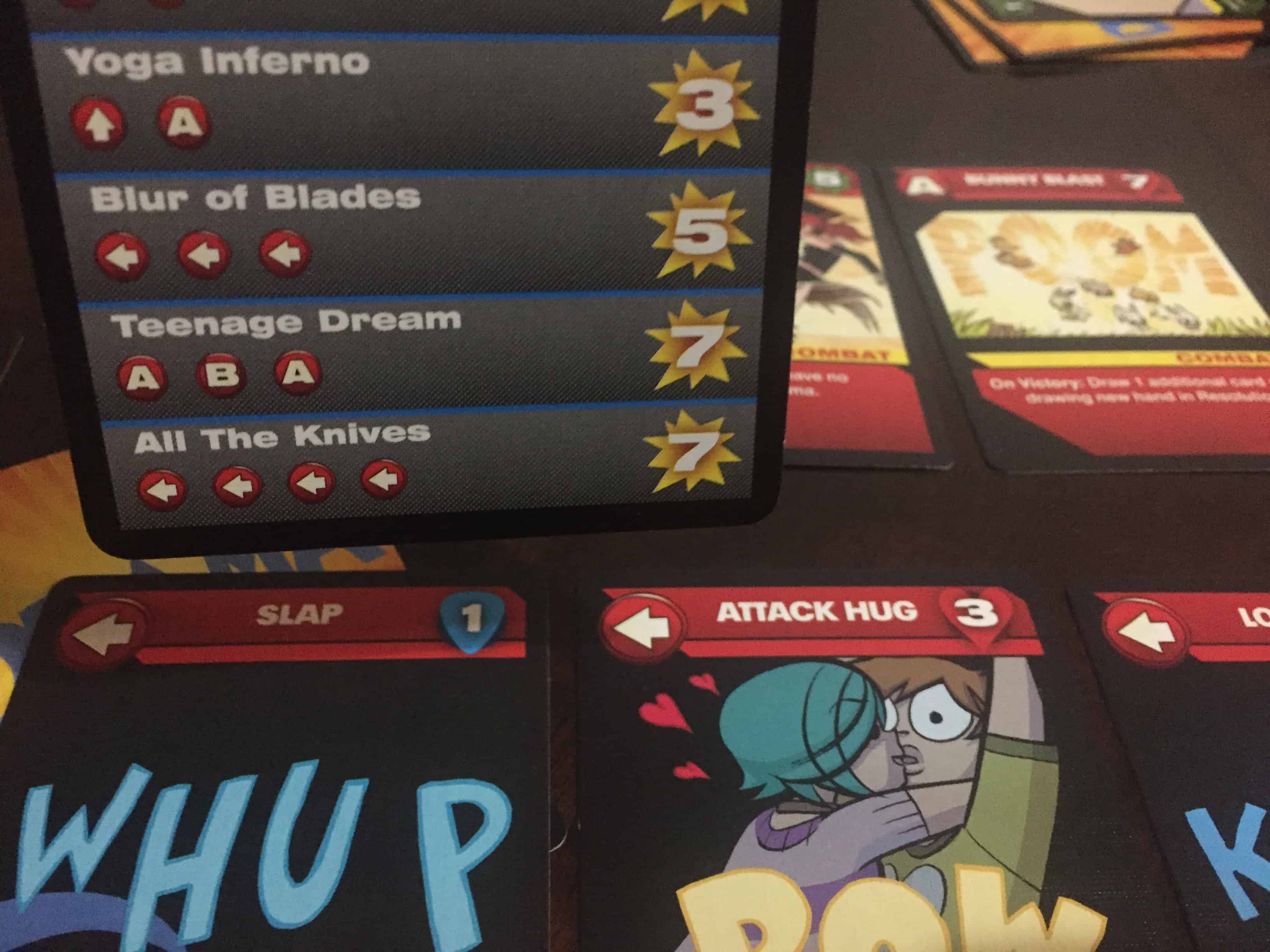

During an optional second phase, you can pick a fight with a challenge card from the market, or fight the evil ex itself. You will discard your whole hand from the last phase, draw up a new hand, and use the red sides of your cards to do battle. Each action card you play gives you one power (called ‘button mashing’). However, you can buff your damage by stringing together arrows and letters printed on your card in certain ways, depending on your character.

Arcade game veterans will immediately recognize the homage. Down, Down-Forward, Forward, Punch = HADOUKEN!! (Let me help you out if you don’t know the reference). When you build your deck, you will need to know what combos your character can do. Then you can buy arrow/ button cards accordingly.

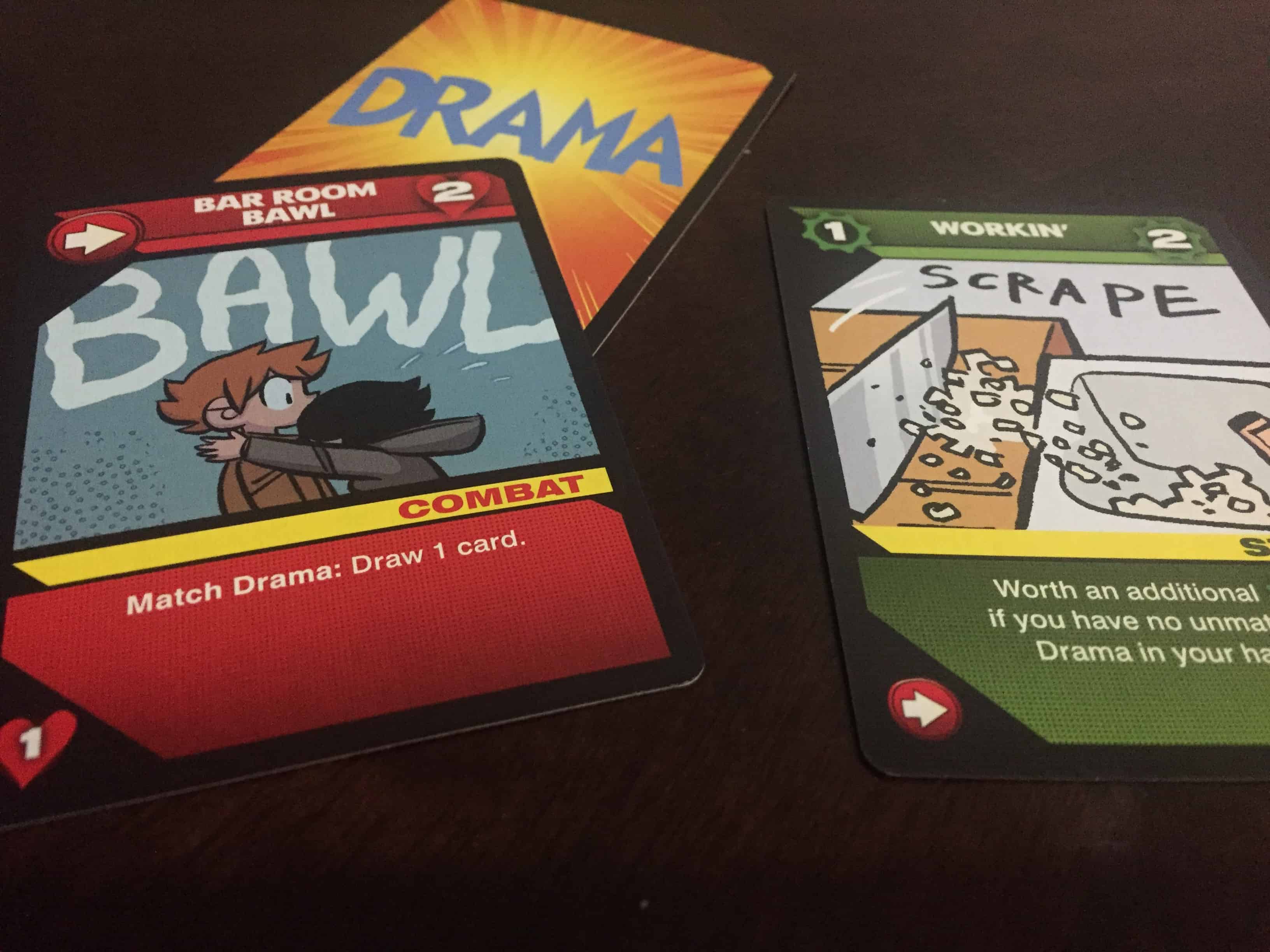

Aside from your action cards, you will also have Drama cards which represent “the complications and baggage in their lives”. Drama cards are blanks that generally gunk up your hand and cause problems in other ways. Most characters will want to find way to “eliminate” them (i.e., trash them), from the game. However, some characters thrive on drama (go, Scott!) and have action cards that combo well with them. Your character cards will tell you which characters could use a little more drama in their lives.

In terms of basic gameplay, that’s it! Despite how intimidating the double sided cards may look, Scott Pilgrim is a simple game. However, you absolutely need to know the following two meta-rules in order to having the best time you can with Scott Pilgrim.

First, before your player phase, you can discard up to two cards from the deck. Second, when you buy a card, you can trash it instead of keeping it in your deck. Aside from the strategic value of denying your opponent needed cards, both of these rules also exist to keep the market moving. Eventually, you will only want certain plot and/ or challenge cards to appear in the market so that you can beat them and score your victory.

You can choose to compete against your friends in a race for points, or you can try to work with your friends and hit a certain point threshold together. If you played the game cooperatively, you have to hit twice the point threshold of the Evil Ex, and you have to do so in a preset number of rounds. However, you generally do the exact same things on a given turn that you would in the competitive game.

What I liked about Scott Pilgrim’s PLCG

For me personally, I don’t have a lot to say about how much the game echoes the comics. I’d be curious to know what fans of the comic books really thought of how it represents the theme. From a purely aesthetic perspective, though, I found the game very pleasant. With over 200 cards, a few repeated assets would have been forgiven. Instead, you get a whole bunch of (presumably) original art, drawn and/ or approved by the original artist.

The action cards themselves are quite conscious of theme tie-ins, where possible. For example, a Workin’ card worked better without any other Drama cards in hand, but the Bar Room Bawl became better when paired with a Drama card. Little nods like that amused me greatly.

In addition, at the end of a typical game, you will probably have a number of Plot cards in front of you that you could use to tell a story about yourself. For example, you could say that you Crashed with Friends and worked as a Barista until you could afford time in a Recording Studio and eventually earn enough Fans to become famous. That kind of thing.

With regard to mechanisms. I admit that I give games extra credit when games try to tweak old formulas. Instead of a reskin in the Legendary System or (worse) of an Exploding Kittens-type game, Scott Pilgrim’s PLCG takes some chances with the deckbuilding genre.

The double-sided cards, for example, could easily have gone wrong and confused people more than anything. However, I got used to them very quickly due to some very simple design choices. A card in the market, for example, costs the same amount of resources whether it’s on the green or red side. Also, every action card as an icon on its bottom left corner that gives a hint as to its flip side.

As an example, if I know my character uses lots of work resource for acquisition and lots of left arrows for combat, I know to zero in on those type of cards. I like when games give me lots of options, but also ways to mentally narrow those options to make optimal choices.

I also enjoyed how often you churned your deck. A lot of deckbuilders tantalize you with fun, expensive cards, but you don’t get to play them often because they get stuck in your discard pile. Some games solve this issue by allowing purchases to go straight into your hand. In Scott Pilgrim, you draw a new hand for both the acquisition and combat phases. You also have lots of options for thinning your deck, or earning extra draw, even despite (or sometimes because of) the Drama cards.

Finally, I had fun with both the cooperative and competitive versions. I would say that I enjoyed my solo/ cooperative games a bit more, but I naturally LOVE coop games, so of course I’m going to say that! What I will say, though, is that I felt both versions seemed to work as intended, with neither truly lagging behind.

What I didn’t like about Scott Pilgrim’s PLCG

Looking around BGG, reddit, and a few other places where people have played the game, I’ve seen some very mixed reviews. Neither Anthony nor Chris on the main BGA podcast liked the game.

When Anthony and Chris demoed the game, their teacher did not show them those two deck-cycling rules I mentioned above – discarding at the top of the turn and immediately discarding purchased cards – to keep the market moving and generate greater chances at needed cards. Anthony described having multiple turns where he had nothing to buy and no challenges to beat. If they churned the market more often, they could have avoided being frozen like that.

It was a teaching fail, for sure; their game teacher should have pointed those out. However, these are easy rules to miss and probably shouldn’t be necessary. Many deckbuilders do not need tricks like this to keep things flowing. For example, I’ve been playing a fair amount of Aeon’s End. The deckbuilding in that game is friction-less. You rarely feel truly stuck in that game.

This points to what I believe is the main, and most frustrating, flaw of the game. Despite saving all that design space by using double-sided cards, the main deck still has a ton of bloat. The game could have tightened things up a bit by, say, using a one or two resource system, or including more wild cards, or having cards that let you search out challenges from the deck. Instead, the deck-cycling tricks feel like pinned-on mechanical hacks to the system, rather than integral parts of it.

I’ve played Scott Pilgrim’s PLCG solo a bunch of times, so I’ve seen games of all kinds. Sometimes, things magically come together and I get going right away. Sometimes I look at an opening market, then just shake my head and reshuffle. I think it all evens out, over the long term. However, you can easily get a bad first impression. I know that’s a danger in many games, but it feels more likely to happen here.

Speaking of things slowing down, I don’t think I will ever, ever play this game with four players again, unless they all know what they are doing. Very often, players go through both the acquisition and combat phases of their turn, each of which can take a while. Sometimes the perfect card for your deck will leap out at you. Other times, though, you’ll have to puzzle out between a few choices. Do you go for a power that trashes your junky cards, or do you go for arrows to make better combat combos? When do you make the turn to buying victory point cards? Should I spend money on cards for me, or do I need to trash something my opponent wants?

Waiting for three other players to figure that (and other stuff) out isn’t bad, in itself. However, a) you don’t have much to do outside of your turn and b), players will often resolve a whole other phase afterwards. This generates way too much downtime for what should be a quick card game. Therefore, I’d recommend keeping the player count down, especially among people who are just learning it.

Final Verdict/ Who is this game for

I acknowledge some rather significant flaws in basic design here. If other reviewers had a worse time with the game, I can see where they are coming from and have no desire to disagree.

I did think, though, that I experienced enough positive elements to keep me engaged. The deckbuilding engine, as well as the overall resource/ combat economy, felt different enough to stand out. Also, on an aesthetic level, the game really delivers. All in all, I enjoyed my plays of Scott Pilgrim’s PLCG and will happily play more, even though I’m not all that attached to the IP.