For the last three years, I have conducted research designed to support the viability of board games as a pedagogical tool in the writing classroom. The central thesis of that work is that games are as thematically rich and rhetorically complex as any novel, film, or other piece of art that we commonly hold up as a representative work in educational settings. Any single board game can be used to teach elements of cooperation, communicative emergence, or the challenges of historical decisions when presented in the right light. But that does not mean all games are well-suited to the classroom. There will always be tabletop games that are too long, too complex, too rules-heavy, or too combative to support an inclusive, intellectually stimulating environment.

That’s why games like Rising Waters are so important to the effort of introducing tabletop gaming as a viable pedagogical tool in different classroom settings. Designed to represent a tenuous historical period and difficult themes that are often overlooked in that period, yet containing compelling, engaging mechanics that make the game engaging as an act of play, Rising Waters succeeds in its goal of providing a suitable modern cooperative game for educational purposes.

Listen to the audio review of Rising Waters on episode 472 (timestamp: 35:30)

A Marriage of Theme and Mechanics

To discuss Rising Waters’ mechanics is to discuss its theme, as the two are carefully intertwined. This is a game about the impact of a systemically racist approach to flood control along the banks of the Mississippi River in Mississippi at the start of the 20th century.

After decades of the US Army Corp of Engineers prioritizing higher and higher levees, floods in the area grew worse with waters more turbulent and concentrated than ever. When a levee broke, the devastation on the communities in the flood’s path would be monumental. This came to a head in the Spring of 1927 when the Mississippi overflowed its banks and devoured entire communities.

The challenges of that time extend beyond poor infrastructure planning and to the way in which African American communities were treated. Often concentrated in the low-lying areas where flooding was likely to be worse, African Americans were also often taken to Rescue Camps far from their homes where they would be encrypted to help build new levees and engage with the flooded countryside in a dangerous way.

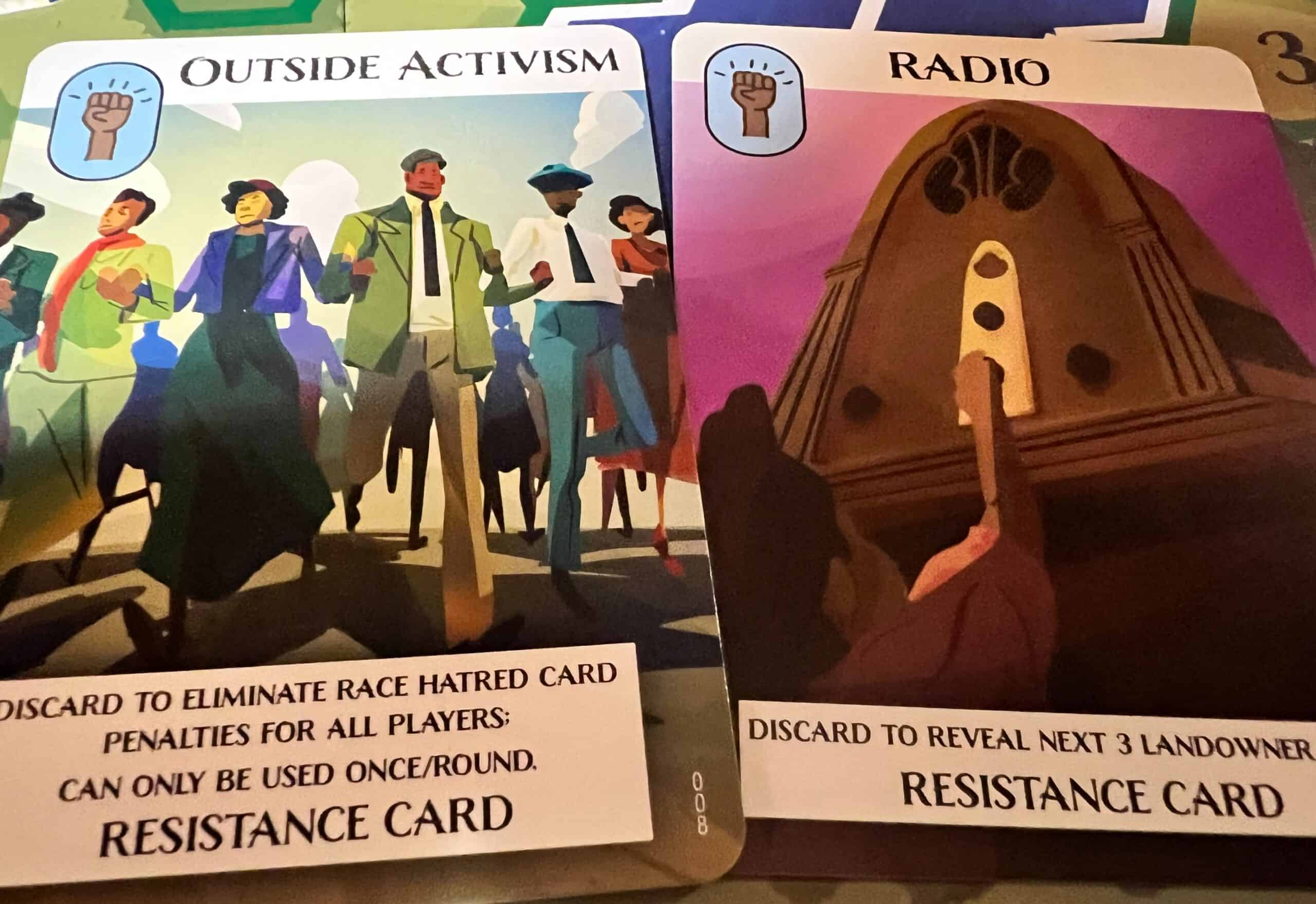

Rising Waters tasks players with representing these communities, and the cards reflect it. Along with staples of the African American community of the time and place such as Church, Blues music, and Gardens, players will be given resist cards that they can use to counter the negative effects of cards like “Force” which requires players to give up their resources or “Race Hatred” that drives direct attacks on player communities.

At every step, the game integrates the theme of the time with the actions players take, marrying player agency with the act of resistance, perseverance, and love for friend and neighbor to illustrate not just the injustices wrought on Mississippi’s African American population but also the response of that population to those injustices.

A Familiar Cooperative Experience

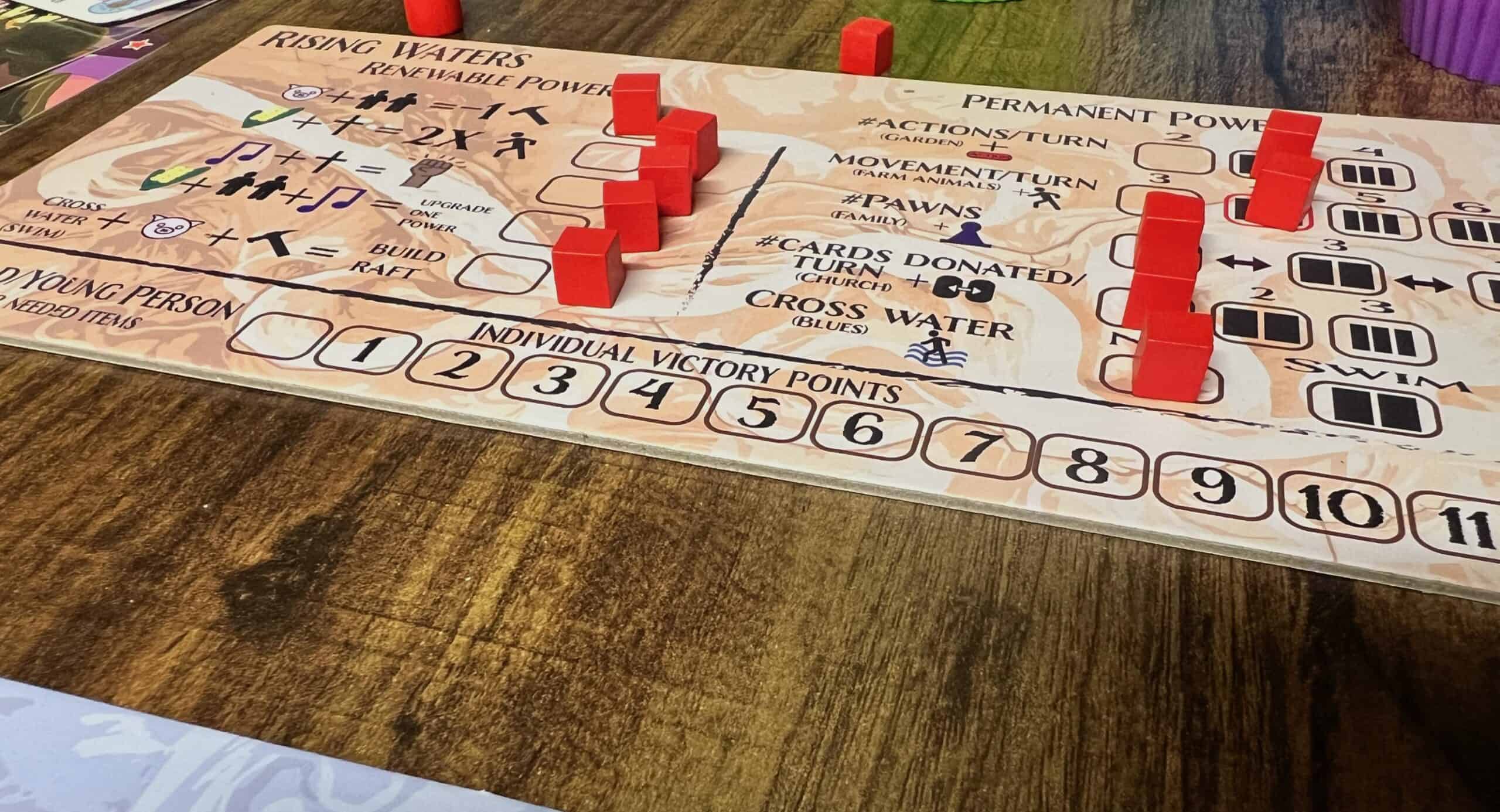

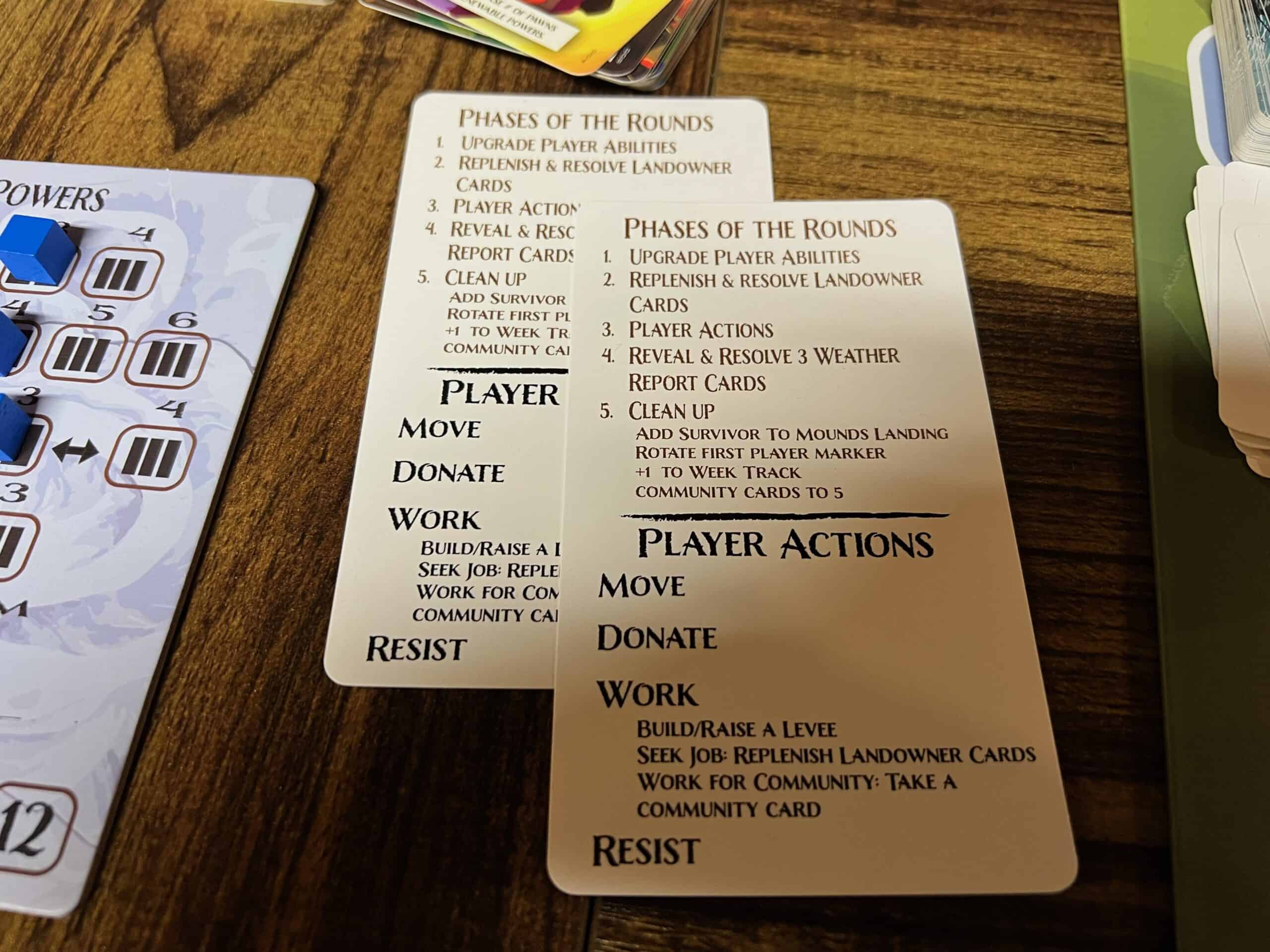

Rising Waters wisely uses a cooperative structure to represent the communal efforts to stave off greedy landlords and protect their homes from rising flood waters. Each player is given a player board with several possible action paths for upgrades. At the start of the game, each player will have two actions per turn during a round. This can be upgraded, however, by spending Garden cards from their hand (up to 4 actions). Other actions can similarly be upgraded, including the number of spaces a pawn can move with the Move action, the number of cards that can be “donated” with the Donate action, and the ability to “Swim” or cross water without having to spend extra cards.

Each round, players will hold a new hand of cards that they can spend in pairs and sets to upgrade these actions for greater efficiency. At the same time, they must hold on to some cards, especially Resist cards that are likely to protect against events in the deck that might be harmful. This balance of upgrades and hand-building is important because it shows the difficulty of the decisions that need to be made in such a time of crisis. Hold on to the pieces of your community that mean so much to you or selectively give some up to have a better chance to survive what’s coming.

On a player’s turn, they will take those now upgraded actions to move their pawns on the map, build or upgrade levees to protect land from overflowing river banks and donate cards to the recovery effort to localize camps and reduce the risk of having to traverse the full map to deliver survivors.

After player actions, the river takes its turn. The rains fall and the water rises. This is the crux of the game, where players will learn if their efforts to shore up the levies downriver were sufficient or if it will rain heavier and more concentrated in one area than another—at the mercy of the randomness of a deck of cards.

One element that might prove challenging is the way in which the game handles difficulty. The “easy” version of the game removes several mechanics, including some of the more impactful event cards, the relief camps, and community goals, effectively streamlining the game to be fairly simple. This makes for a shorter experience that is easier to teach and reduces the risk of quick, catastrophic failure (as is common for new players in many cooperative games). The full game with the Spring 1927 rules, is much harder, shrinking the area of effect for movement and levies, introducing more cards to the deck (and reducing the Job Offers available), and complicating the rescue of survivors. This version of the game is a more complete historical experience but is also quite a bit more difficult and might prove too much of a frustration for less experienced players (such as students).

Designed for the Classroom

Rising Waters is not just a historical game that might be a good fit for the classroom. It is explicitly designed with educational use in mind. The game’s designer, Dr. Elizabeth (Scout) Blum, is a history professor at Troy University in Alabama. Her company, Mockingbird Games, specializes in educational board games. Rising Waters was submitted to the 2021 Zenobia Awards contest, finishing 13th overall.

With the game, Blum and the publisher have constructed a 100+ page curriculum guide to help instructors successfully integrate the game into class as a pedagogical tool and not just a “fun” distraction. That’s not to say the game isn’t fun, but Blum’s curriculum guide provides a framework for exploring the explicit and implicit messages of the game. Starting with nearly 20 pages of historical context, instructors can provide students with the necessary background to understand not just how the flood of 1927 occurred, but the history of race relations in the region and the ultimate reaction to white racism before and during the flood.

Other sections address how “The Mechanic is the Message,” a nod to Brenda Romero’s groundbreaking use of tabletop game mechanics to present explicit messaging around social topics. The game effectively plays with this idea, giving players agency through difficult choices about how they allocate community cards, respond to threats and racism, and prepare for future flooding.

Finally, the curriculum guide provides an explicit set of materials for preparing students to play and discuss Rising Waters in the classroom. One of the areas I’ve spent the most time refining my own tabletop courses is teaching games. What materials should students be responsible for and what am I responsible for? When do they need to know the game? And how thoroughly should a game be taught before and during play? Rising Waters is a relatively complex game for anyone who has not played comparable games before. Without a baseline understanding of games like Pandemic, the cognitive load will be quite high, even for college students, so it’s crucial to have an intentional approach to teaching the game, with ample resources to support student success in engaging with the mechanics.

Blum also offers a series of assignment recommendations around issues of agency, racism, technology, narrative discussions, and analysis of the game’s mechanics, covering a wealth of different options depending on the subject of a course and the students’ age and experience.

Final Assessment

Rising Waters is a unique game in a number of ways. It takes the approach of a “serious game,” addressing real-world issues in the context of a specific historical event, but it is designed to be fun and replayable in a way that some (not all) serious games are not. It offers an easier mode of the game that is more adaptable to shorter class periods and students with less or no gaming experience but also offers a much more difficult game mode for more experienced players with more time to explore its intricacies.

At its heart, the game is reminiscent of great cooperative experiences like Pandemic and Forbidden Island, but in presentation, it has more to say, drawing more substantial comparisons to Freedom: The Underground Railroad or The Grizzled, well-constructed mechanical systems with messaging that allows for a more robust conversation about the experience of playing the game.

I found Rising Waters to be a powerful pedagogical tool that fits well within the framework of a course designed to explore complex topics in non-traditional ways. By exploring player agency in the context of a complex system that represents a difficult chapter in American history, Rising Waters is an engaging, academically rich text that offers a range of ways to engage with its mechanics, theme, and presentation. For gamers, I rate this as a “play” on the BGA scale. For educators, I offer a more robust endorsement both for the game’s rhetorical rigor and for the supportive materials that make integrating it into your curriculum seamless.